Having a list makes it easy for us to tick off those bad chemicals that nobody wants to live with. And in the building industry there have been a proliferation of lists which identify chemicals of concern: the Perkins & Will Precautionary List, the LEED Pilot 11 and the Living Building Challenge Red List, among others. And make no mistake, we think it’s critical that we begin to develop these lists, because we all need a baseline. As long as we need to eat and breathe, toxics should be an important consideration. We just have a problem with how these lists are used.

So let me explain.

First, lists for the most part are developed on the basis of science that usually occurred five or 10 years ago, so they can (though not always) be lagging indicators of safety to humans and the environment. (But that’s a minor point, just wanted us to remember to maintain those lists.)

When using lists, it’s important to remember the concept of reactive chemistry: many of the chemicals, though possibly deemed to be benign themselves, will react with other chemicals to create a third substance which is toxic. This reaction can occur during the production of inputs, during the manufacture of the final product, or at the end of life (burning at the landfill, decomposing or biodegrading). So isn’t it important to know the manufacturing supply chain and the composition of all the products – even those which do not contain any chemicals of concern on the list you’re using – to make sure there are no, say … dioxins created during the burning of the product at the landfill, for example?

It’s also important to remember that chemicals are synergistic – toxins can make each other more toxic. A small dose of mercury that kills 1 in 100 rats and a dose of aluminum that will kill 1 in 100 rats, when combined, have a striking effect: all the rats die. So if the product you’re evaluating is to be used in a way that introduces a chemical which might react with those in your product, shouldn’t that be taken into consideration?

So, O.K., the two problems above would be extremely difficult to define – I mean, wouldn’t you need a degree in chemistry, not to mention the time and money, to determine if these could occur . The average consumer wouldn’t have a clue. Just wanted you to know that these problems do exist and contribute to our precautionary admonition regarding lists.

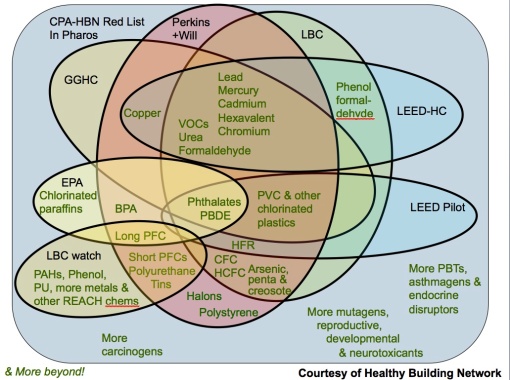

Each list has a slightly different interpretation – and lists different chemicals. The Healthy Building Network published this Venn diagram of several of the most prevalent lists used in building materials:

The real reason we don’t like the way lists are used is that people see the list, are convinced by a manufacturer that their product doesn’t contain any of the chemicals listed, so without any further ado the product is used.

What does that mean in the textile industry, for example?

By attempting to address all product types, most lists do not mention many of the toxic chemicals which ARE used in textile processing. In the Living Building Challenge Red List, no mention is made of polyester, the most popular fiber for interiors, which itself is made from two toxic ingredients (ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid – both carcinogens, neither of which are on the list). That means a fabric made of polyester – even recycled polyester – that has been processed using some pretty nasty chemicals – could be specified. Chemicals which are commonly used in textile processing and which are NOT included on the Living Building Challenge Red List, for example, but which have been found to be harmful , include:

| Chlorine (sodium hypochlorite NaOCL); registered in the Toxic Substances Control Act as hypochlorous acid ; sodium chlorite |

| Sodium cyanide; potassium cyanide |

| sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) |

| Sodium sulfide |

| APEOs ( Alkylphenolethoxylates) |

| Chromium III and VI (hexavalent chromium) |

| Zinc |

| Copper |

| pentachlorophenol (PCP) |

| permethrin |

| Dichloromethane (DCM, methylene chloride) |

| Tetrachloroethylene (also known as perchloroethylene, perc and PCE) |

| Methyl ethyl ketone |

| Toluene: toluene diisocyanate and other aromatic amines |

| Methanol (wood alcohol) |

| Chloroform; methyl chloroform |

| Arsenic |

| Phosphates (concentrated phosphoric acid) |

| Dioxin – by-product of chlorine bleaching; also formed during synthesis of certain textile chemicals |

| Benzenes and benzidines; nitrobenzene; C3 alkyl benzenes; C4 alkyl benzenes |

| Sulfuric Acid |

| Optical brighteners: includes several hundred substances, including triazinyl flavonates; distyrylbiphenyl sulfonate |

| Acrylonitrile |

| ethylenediaminetetra acetic acid [EDTA] |

| diethylenetriaminepenta acetic acid [DTPA] |

| Perfluorooctane sulfonates (PFOS) |

In the case of arsenic (used in textile printing and in pesticides) and pentachlorophenol (used as a biocide in textile processing) – the Living Building Challenge Red List expressly forbids use in wood treatments only, so using it in a textile would qualify as O.K.

Perhaps we should manufacture with a “green list” in mind: substituting chemicals and materials that are inherently safer, ideally with a long history of use (so as to not introduce completely new hazards)?

But using any list of chemicals of concern ignores what we consider to be the most important aspect needing amelioration in textile processing – that of water treatment. Because the chemicals used by the textile industry include many that are persistent and/or bioaccumulative which can interfere with hormone systems in people and animals and may be carcinogenic and reprotoxic, and because the industry often ignores water treatment even when it is required (chasing the lowest cost) the cost of dumping untreated effluent into our water is incalculable.

The textile industry uses a LOT of water – according to the World Bank, 20% of industrial freshwater pollution is from the textile industry; that’s another way of saying that it’s the #1 industrial polluter of water on the planet. In India alone textile effluent averages around 425,000,000 gallons per day, largely untreated[1]. The chemically infused effluent – saturated with dyes, de-foamers, detergents, bleaches, optical brighteners, equalizers and many other chemicals – is often released into the local river, where it enters the groundwater, drinking water, the habitat of flora and fauna, and our food chain. The production of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were banned in USA more than 30 years ago (maybe that’s why they’re not listed on any of these lists?), but are still showing up in the environment as unintended byproducts of the chlorination of wastes in sewage disposal plants that have a large input of biphenyls (used as a dye carrier) from textile effluent.[2]

Please click HERE to see the PDF by Greenpeace on their new campaign on textile effluent entitled “Dirty Laundry”, which points the finger at compliant corporations which basically support what they call the “broken system”. It asks corporations to become champions for a post toxic world, by putting in place policies to eliminate the use and release of all hazardous chemicals across a textile company’s entire supply chain based on a precautionary approach to chemicals management, to include the whole product lifecycle and releases from all pathways.

Another problem in the textile industry which is often overlooked is that of end of life disposal. Textile waste in the UK, as reported by The Ecologist, has risen from 7% of all waste sent to landfills to 30% in 2010.[3] The US EPA estimates that textile waste account for 5% of all landfill waste in the U.S.[4] And that waste slowly seeps chemicals into our groundwater, producing environmental burdens for future generations. Textile sludge is often composted, but if untreated, that compost is toxic for plants.[5]

What about burning: In the United States, over 40 million pounds of still bottom sludge from the production of ethylene glycol (one of the components of PET fibers) is generated each year. When incinerated, the sludge produces 800,000 lbs of fly ash containing antimony, arsenic and other metals.[6]

These considerations are often neglected in looking at environmental pollution by textile mills[7] – but is never a consideration on a list of chemicals of concern.

So yes, let’s recognize that there are chemicals which need to be identified as being bad, but let’s also look at each product and make some kind of attempt to address any other areas of concern which the manufacture of that product might raise. Using a list doesn’t get us off the hook.

No comments:

Post a Comment